Artist statement on Local Produce: Aluminium slabs - 6 metres, 6 tonnes each

Australia is estimated to hold reserves of more than 3 billion tonnes of commercial grade bauxite, from which alumina – the powdery white oxide of aluminium – is made. About 2.5 tonnes of bauxite is required to produce one tonne of alumina. Australia produces 30% of world alumina, and one million tonnes is shipped each year to Newcastle. About 500.000 tonnes of aluminium is exported each year from the port of Newcastle. Tomago's smelter at nearby Kooragang employs over 1000 people, and operates non-stop.

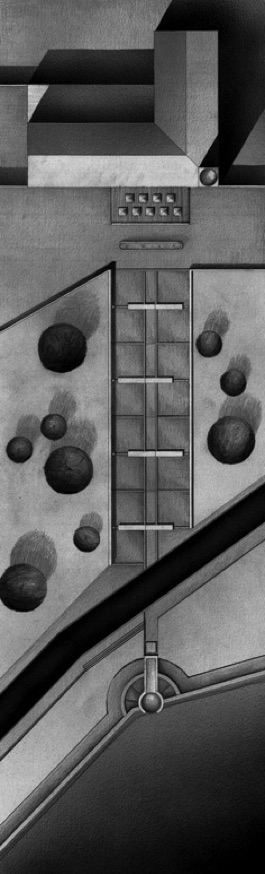

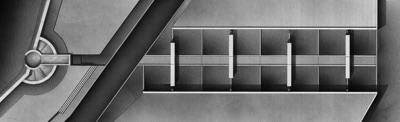

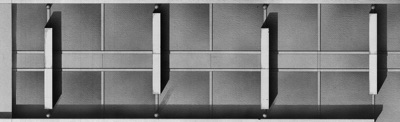

Eight aluminium slabs are placed ready to ship in the forecourt of customs house. The average slab is 6 metres long and weighs 6 tonnes. The combined weight of the installed slabs is 48 tonnes. This is sufficient to produce 50.000 kilometres of alfoil, enough to circumnavigate the planet.

Local produce is a collaborative project by Michael Chapman and Richard Tipping, commissioned for Back to the City, 24 January to 17 February 2008.

Local Produce

Essay by Richard Tipping and Michael Chapman

The Macquarie Dictionary defines Aluminium as a silver-white metallic element, light in weight, ductile (that is, capable of being hammered out thin, and able to stand deformation under a load without fracture), malleable (that is, capable of being extended or shaped by hammering or by pressure with rollers) and not readily oxidised or tarnished. It occurs combined in nature in igneous rocks, shales, clays, and most soils. It is widely used in alloys and for lightweight utensils, castings, aeroplane parts, etc.

Australia is estimated to hold reserves of more than 3 billion tonnes of commercial grade bauxite, from which alumina – the powdery white oxide of aluminium – is made. About 2 ½ tonnes of bauxite is required to produce one tonne of alumina. Australia produces 30% of world alumina, and one million tonnes is shipped each year to Newcastle. 500 000 tonnes of aluminium is exported each year from the port of Newcastle. Tomago's smelter at nearby Kooragang employs over 1000 people, and operates continuously every day of the year.

Eight aluminium slabs are placed ready to ship in the forecourt of Customs House, the historical site for the scrutiny of goods. The average slab is 6 metres long and weighs 6 tonnes. The combined weight of the installed slabs is 48 tonnes.

The aluminium made at the Tomago plant near Newcastle is produced in various kinds, with varying alloy content to suit different purposes. Aluminium is used extensively in the building industry with aluminium window frames, for example, and in the beverage industry for drink cans. There are billets, ingots and slabs, which vary in size and shape. The slabs which we have used at Customs House are used for making alfoil. This is sufficient to produce enough alfoil to stretch from Sydney to Singapore.

Aluminium foil is an expensive looking material. At the supermarket, we bought a 70 metre roll, 30 cm wide, for $10. This is discounted because of the large length – it weighs 670 grams. We have calculated that 48 tonnes of aluminium will make 6000 kilometres of aluminium foil of this width. If 70 metres costs $10 retail, then the retail value of 6000 kilometres should be a bit over 857 thousand dollars. The wholesale value of the eight slabs is more like $125.000.

Aluminium foil looks like perfection, like a promise of protection, like a glittering wrap, all surface, shimmering with attraction, reflecting the material world around itself. When you pull it from its roll, and tear on the convenient serrated metal edge to the cardboard package, the endless roll becomes segmented into domestic scale, into useable slices of metal sheet which the kitchen adores: wrapping and baking apples and fish, covering the roasting pan, sealing freshness inside for the freezer's delayed gratifications. It is an obsessive package. It is all consumer lust. Stare into the mirror of the foil, and see consumption not redemption. This dense materiality, this lightness, this disposable brilliance --- marker of time, mortality, appetite, desire. Marker of cleanliness, germ-free guarantees, pulled, stretched out, torn off, folded, shaped around things, peeled off from things, re-exposing the protected, then simply crushed. Crush. Disposed, into the bin, and away to landfill.

All of this heaviness, this weight and seriousness of the solid, this bulk and hardiness, this scale and the apparent permanence of the hefty slabs, all of this leads to a metamorphosis to the insubstantial, to disappearance.

There are no words or letters made with the slabs. Perhaps writing is frozen speech, and the sun warming the slabs out there in the plaza in front of old Customs House makes conversation swing into the breeze. The work is all implication. What is this, where is it from, who put it here, how is it made, why? Why this not that? Where to now?

Sculpture is about place as well as space and solid forms. Sculpture is also a relationship with the body of each person experiencing it, as they move through the surrounding dimensions of its occurrence.

This aluminium sits for a moment between states. It was bauxite ore, then alumina, now aluminium alloy, and will soon be aluminium foil. All of its presence is temporary, it is in a state between states. Think of all the alfoil reflecting in the sun. Think how much electricity it took to make this fanciful foil. It is another folly. We are fossil fools.

This is Local Produce, made and ready to ship. Locality is all. There is no there there. It is all here.

© Dr Richard Tipping and Dr Michael Chapman. First published in xxxxxxxx

Line drawings by Michael Chapman. Photographs by Richard Tipping.

Protesting against coal-powered smelting

(c) Richard Tipping All text and images are copyright and protected by international legislation. See the Copyright page for more information. For permission to use any of these materials please see Contact page